Gaming Guides

Gaming Guides

Latest articles

-

Car Guides

12 Best Budget Project Cars

Are you tight on cash but hungry for your next project car? Then, you have come to the right place. Here are the best project cars for gearheads on a budget. -

Gaming Guides

Ultimate Forza Horizon 4 Drift Tune Guide

Looking for a fantastic base drift tune for Forza Horizon 4 that you can tweak to match your preferences? Check out our Forza Horizon 4 drift tune guide. -

Car Guides

Best RC Drift Cars Guide For 2024

Are you eager to get into drifting, but your bank balance is holding you back? RC drift cars present the perfect opportunity to get your drifting fix. -

Engine Guides

Ultimate Honda K24 Guide – Everything You Need To Know

The Honda K24 is one of the most legendary engines to come out of Japan. In this guide, we're taking a look at everything you need to know about it. -

Miata Tuning

Ultimate Miata Engine Swap Guide

Want to know the best Miata engine swap out there? Join us as we explore the best options available to increase the humble roadster's performance. -

Car Guides

BMW M3 Vs M4 – What’s The Difference?

Do you have your eyes set on the BMW M3 and M4 but can't decide which one to get? We're putting them head to head in our BMW M3 vs M4 comparison. -

Gaming Guides

Top 10 NFS Heat Best Cars

Since Need For Speed Heat has no shortage of incredible rides, we’re looking at the 10 quickest rides in the game in our NFS Heat best cars guide. -

Gaming Guides

Best GR3 Car GT7 – What Are The Top Picks?

Join us in our best GR3 car GT7 guide and discover why the GR3 category is one of the most competitive parts of Gran Turismo 7. -

Gaming Guides

Ultimate VR Racing Games Guide For 2024

As VR continues to revolutionize gaming, we take a look at the best VR racing games on the market that provide the ultimate Virtual Reality racing experience. -

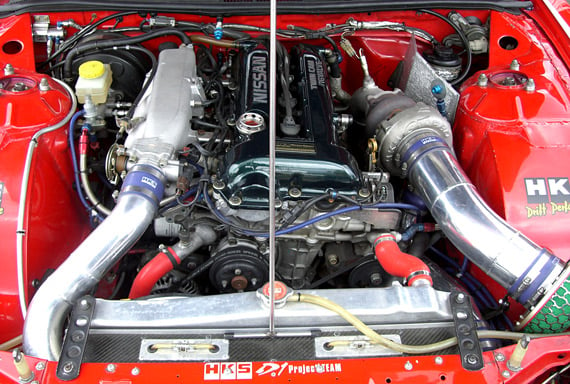

IS300 Tuning

Ultimate 2JZ-GE Turbo Kit Guide

Toyota’s 2JZ-GE engine has an insane amount of untapped potential. This guide will help you find the best 2JZGE turbo kit to suit your preferences. -

Beginner Guides

How Long Can a Car Sit Without Being Driven?

Thinking of storing your pride and joy for a while? In this article, we'll tell you how long can a car sit without being driven and more things to consider. -

Engine Guides

Toyota 2GR-FE Guide – Everything You Need To Know

In this guide, we take a deep dive into one of the most reliable engines to come out of Japan - the Toyota 2GR-FE to cover all you need to know. -

Gaming Guides

Ultimate Forza Horizon 4 Best Drift Car Guide

Are you looking for the best drift cars in Forza Horizon 4? Look no further; we're listing our favorite cars in this Forza Horizon 4 best drift car guide. -

Gaming Guides

9 Best Free Drift Hunters Alternatives

We present the nine best free Drift Hunters alternatives for the Drift Hunters fan that has mastered the original game and is looking for the next challenge. -

Gaming Guides

The 22 Fastest Cars In Forza Horizon 5

Are you looking to overtake your rivals in FH5? We’re checking out 22 of the world’s most exotic hypercars as we compare the fastest cars in Forza Horizon 5. -

Car Guides

Ultimate Nissan 350z Guide – Everything You Need To Know

Nissan's 350z is the JDM performance car of this decade and to celebrate we have assembled all the information you will ever need to know on the mighty Z33. -

G37 Tuning

Infiniti G37 Exhaust Guide

Looking for a performance G37 exhaust? You've come to the right place. We compare nine of the best G37 exhausts available to help you find your perfect system. -

Gaming Guides

Forza Horizon 5 Houses – All You Need to Know

We deep dive into everything you need to know about Forza Horizon 5 Houses. Learn why all the houses in Forza Horizon 5 are essential and how to unlock them. -

Car Guides

15 Best JDM Cars Of The Nineties

We present fifteen of the best JDM cars of the nineties and check out the latest news on their upcoming state-of-the-art successors. -

Beginner Guides

43 Inspiring Paul Walker Quotes About Cars, Movies, Life & Family

This year marks what would have been deceased action hero Paul Walker's 50th year and to honour that we have assembled 43 of his most memorable quotes. -

Gaming Guides

22 Fastest Cars In Forza Horizon 4

Eager to upset your rivals by getting the fastest car in Forza Horizon 4? We’ve got you covered! This guide covers the 22 fastest cars you'll find in the game. -

370z Tuning

Ultimate Nissan 370Z Supercharger Guide

Looking to turn your Nissan 370Z into a boosted street or track weapon? Not sure about picking the right brand or products? Our 370z supercharger guide has got you covered!

Trending articles

-

Turbocharger Vs Supercharger – What’s Best?

-

1JZ Vs 2JZ – Which Is Best?

-

12 Best Budget Project Cars

-

9 Step SR20 Tuning Guide For Peak Performance

-

Ultimate Nissan 350z Guide – Everything You Need To Know

-

Ultimate 350z Coilover Guide

-

Ultimate S13 Coilover Guide

-

Ultimate Nissan 350z Exhaust Guide

-

43 Inspiring Paul Walker Quotes About Cars, Movies, Life & Family

-

17 Best Drift Cars For Beginners

-

15 Best JDM Cars Of The Nineties

-

Ultimate Nissan 350Z Turbo Kit Guide

-

RB26DETT Vs 2JZGTE – Which Is Better?

-

Toyota 2GR-FE Guide – Everything You Need To Know

-

Best RC Drift Cars Guide For 2024

-

Fastest Cars In GTA Online – The Ultimate Guide

-

Forza Horizon 5 – Release Date, Trailer & More

-

22 Fastest Cars In Forza Horizon 4

-

Ultimate Honda B16 Guide – Everything You Need To Know

-

Nissan 350z Tuning Guides

-

Nissan 370z Tuning Guides

-

Subaru BRZ Tuning Guides

-

Scion FRS Tuning Guides

-

Toyota GT86 Tuning Guides

-

Lexus IS300 Tuning Guides

-

Honda S2000 Tuning Guides

-

BMW E36 Tuning Guides

-

Nissan S13 Tuning Guides

-

Infinity G35 Tuning Guides

-

Infinity G37 Tuning Guides

-

Mazda Miata Tuning Guides

From the commmunity

Proudly supporting

-

Crisis

We are the national charity for homeless people. We help people directly out of homelessness and campaign for the changes needed to solve it altogether. -

Feed Up Warm Up

We're Feed Up Warm Up, a homeless charity in Hertfordshire. We offer food and friendship to homeless people in our community who need support.

Our sponsors

-

Epicvin.com

To get a detailed blockchain confirmed report with photos of every sale, number of owners, salvage history, recalls and odometer, visit EpicVIN.com. -

Enjuku Racing

Get superior performance with Nissan aftermarket parts from Enjuku Racing. Shop tuner parts, Japanese performance parts & more.

Our friends

-

A-1 Auto Transport

We feature open air, enclosed transport, door-to-door, and terminal-to-terminal car shipping services. Additionally, we provide high-end and luxury car transport services for vehicles that require careful handling and extra attention to detail. -

180sx.club

The 180sx Club brings you the latest news, car features, buyers guides and wallpapers for Nissan's 240sx, 200sx and 180sx cars. -

Smart Driving Games

Smart Driving Games brings you the best driving games for free.